EU Tech regulations are a case of premature optimization

EU's AI regulations, while well-intentioned, risk stifling innovation. This post examines how premature optimization in tech policy could hinder Europe's competitiveness in the global AI race.

If you enjoy this post (or have comments to add), consider subscribing to my writings on substack — link

“The real problem is that programmers have spent far too much time worrying about efficiency in the wrong places and at the wrong times; premature optimization is the root of all evil (or at least most of it) in programming.” -Donald Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming

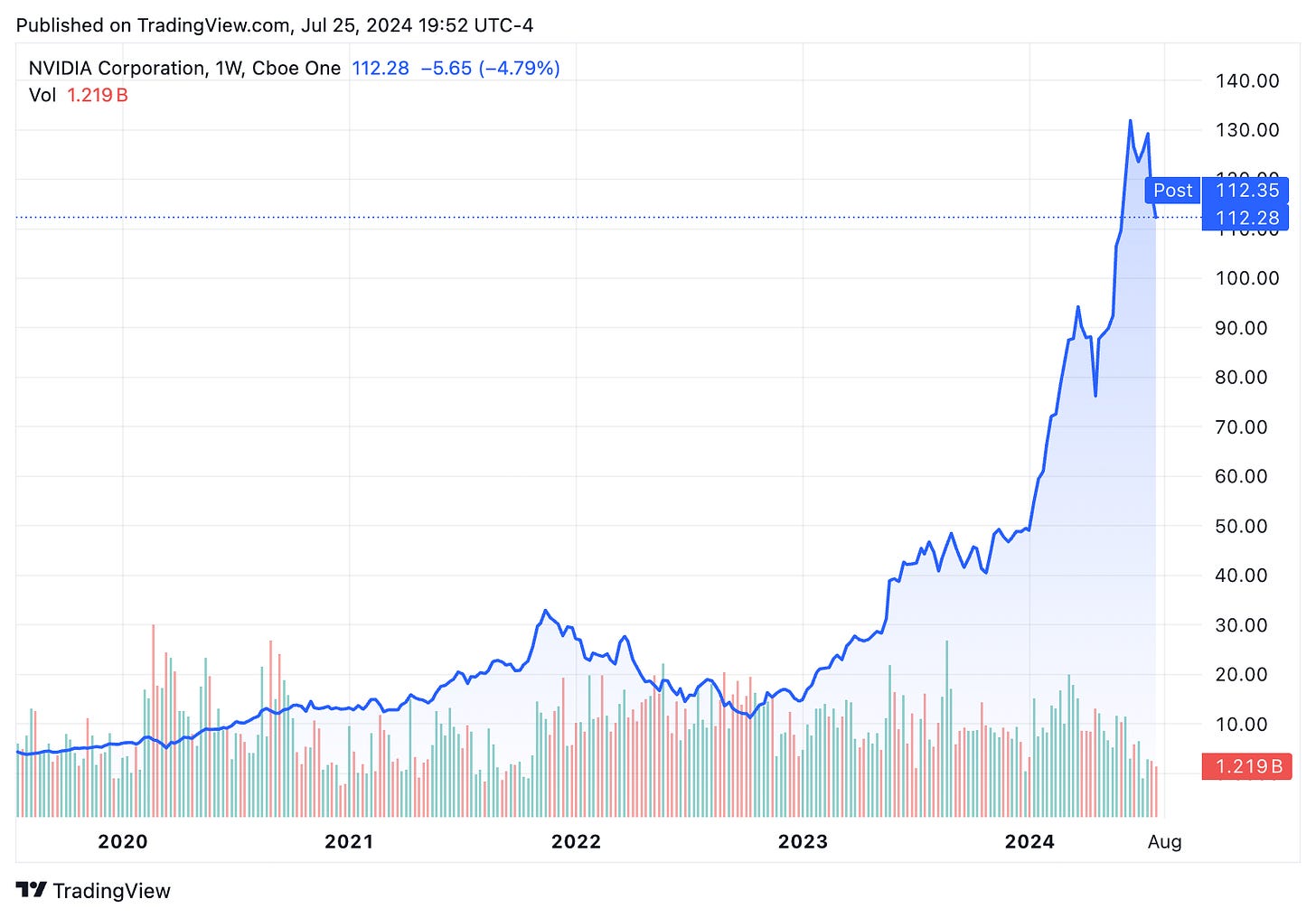

Ever since OpenAI’s ChatGPT went viral in 2022, AI has burrowed its way into the cultural zeitgeist. Fuelled by the AI revolution, stocks like NVIDIA have boomed over the last few years. We went from an age of having Siri, which could barely string together sentences and understand speech, to something many people believe could replace Google altogether within a couple of years.

Along with it came the doomsdayers who think we will soon reach Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and that we need to submit to the AI overlords. A different set of prominent players include the naysayers, who say we are still nowhere close to AGI, and that we need a different, deliberate and concerted effort to reach it. I belong to the latter camp.

This new wave of AI is spearheaded by global players who have invested a tremendous amount of capital both in the form of venture capital and overhead. At the forefront of this are tech giants from the USA, where corporations like Google, Nvidia, Meta, and of course, OpenAI call home. China does not lag far behind, with prominent research units from the country giving US firms a run for their money. Due to the compute hungry nature of the field, giant companies have a sizeable advantage due to the resources they can muster.

The EU, aside from some fringe players like Mistral, has largely been absent from the game. In place of providing impetus to the entrepreneurs who need to step up to the world’s stage, it has introduced a different set of innovations, in the form of regulation. I am of the firm belief that this is a misstep. While I am very much for regulation, as a researcher who has read the EU’s AI act, this seems to be a case of premature optimization for two reasons.

- AI, particularly large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT (which the regulators take clear aim at) are at its infancy. When the technology behind it improves/changes week to week, it seems to me a regulatory nightmare. How does one control what one cannot predict? The EU approach is one way for sure. Regulation through the use of vague blanket statements and buzzword salads that describe the current scene, and hopefully the tech that will come.

- With an already minuscule amount of IP produced by Europe when compared to the rest of the world, the EU risks falling behind. AI giants from the rest of the world need only play according to the rules set by the EU inside the EU. This would enable them to improve by large leaps and bounds, unless the scenario changes.

For this post, I am going to analyze the scenario through the lens of the hottest new AI technology out there, large language models, and through the potential application of two EU regulations — The AI act and the Cyber resiliency act. Through this essay, I want to show how the EU's current regulatory approach risks stifling AI innovation, particularly in the open-source community, and could lead to unintended consequences that may actually hinder the development of safe and beneficial AI. We'll examine the potential economic impacts, including job losses and brain drain, and compare the EU's strategy with more flexible approaches adopted by other regions. Finally, we'll propose alternative paths forward that could better balance innovation with responsible AI governance.

The Current Regulatory Landscape

The EU, as previously mentioned, has put up several regulations with the goal of reining in the big players. The most famous of these is the (general data protection regulation) GDPR in short, which has caused many a knee to buckle.

In this post, I want to bring attention to the problem of premature regulation by analysing two newer regulations, one recently passed, and the other being debated. These are the EU Artificial intelligence act, and the more recent cyber resilience act. Both of these pose grave threats to innovation, especially to those working in the open source space.

The EU AI Act

The AI act, officially passed in March 2024 after two years of discussion, includes numerous phases of compliance. The central point of the act is that it adopts a risk-based approach, categorizing AI systems into four levels:

- Unacceptable risk — Systems that are a clear threat to fundamental rights are outright banned. Think social scoring, manipulative tools.

- High risk — These are those systems that involve significant harm to the health, safety, and fundamental rights of the people or the environment. High risk systems are also subject to strict requirements and obligations before they can be put into the market. Biometric identification and categorization of individuals using biometric data are mentioned here.

- Limited risk — Chatbots and deepfakes are mentioned here, there are a smaller set of obligations which these systems ought to follow, such as that developers and deployers must ensure that end-users are aware that they are interacting with AI.

- Minimal risk — This is unregulated, being a category belonging to AI such as that in video games and spam filters.

The act will be implemented in stages. Starting May 2025, developers will receive guidelines and standards for legal compliance. By August 2025, general-purpose AI systems (like chatbots) must adhere to copyright and transparency rules. Full enforcement for most companies begins in August 2026. However, developers of high-risk AI systems, such as those used in healthcare or finance, have until August 2027 to comply with stricter requirements like risk assessments. Companies that don't comply face fines based on either revenue or fixed amounts. Using banned AI systems carries the heaviest penalty – a fine of €35 million or 7% of global annual revenue.

The majority of the text deals with the regulation of high-risk systems. I am in favour of regulating the technology, but my point is this, however. The field is so rapidly evolving that it is nearly impossible to put a label on whether a system neatly fits into a specific risk category. GPT-4 came out in (insert date). Nearly a year later, OpenAI showcased a demo (insert demo), which added vision and speech-based reasoning. Does it move the technology from limited to high risk now that it has the potential to categorize people based on vision? Even if we disregard that, we also present implicit biases through our writing, which allows us to be identified or categorized. In this case, aren’t LLMs supposed to be high risk, instead of limited? And even if the technology does not currently categorize us explicitly, who isn't to imply that categorization based on traits like race and gender won’t be implicit in the output of the LLM?

Potential pitfalls like these illustrate the downsides of such premature regulation. No one entity can predict exactly where the tech is headed, especially in such gold rush days. Now, this can be construed as a need for even stronger regulation. But there’s a global AI arms race playing out, and when the actors don’t need to play by the same rules, the EU risks falling far behind.

I believe that any innovation is good, even that of the regulatory nature. Left unconstrained, there is a good chance that the technology might be misused. But introducing such stringent regulation even before there is any significant produced in the continent just has the potential to kill technological innovation. There’s an order to this regulatory innovation's implementation that is paramount.

The Cyber Resilience Act (CRA)

The CRA, proposed by the European Commission on September 15, 2022, aims to bolster the cybersecurity of digital products in the EU. It applies to any software or hardware product and its remote data processing solutions, including software or hardware components to be placed on the market separately. The CRA covers tangible digital products, such as connected devices, and non-tangible digital products, such as software products embedded into connected devices.

It requires the manufacturers, importers, and distributors of connected devices and services to comply with the act through certification, reporting, and conformity assessments. The CRA and the AI Act are made with the idea of complementing each other by setting cybersecurity standards for high-risk AI systems. Non-compliance may attract substantial fines, potentially reaching up to €15 million or 2.5% of global turnover, whichever is higher. These requirements could pose significant complexities for AI developers and companies, especially those in a really high amount, especially for the smaller operators in the EU.

Now, what I find most concerning is the part of the CRA that deals with regulating open source software. As it stands, the majority of groundbreaking work in this new wave of AI is done inside giant corporations, who tend to close their work off from the rest of the world to protect their moat. Open source operators have also tried to close the gap, however. I believe the CRA might change that. Currently, in the final “trilogue” phase of the legislative process, the CRA will require products, including open source software, to be accompanied by information and instructions for the user. Creators will need to perform risk assessments and produce technical documentation and, for critical components, have third-party audits conducted. Discovered security issues will have to be reported to European authorities within 25 hours. The CRA is expected to be followed up by the Product Liability Directive (PLD) which introduces compulsory liability for software.

A Case for Regulatory Caution

As an open source developer, I'm deeply concerned about this wave of premature regulation. It threatens our ability to freely distribute our work and collaborate effectively. We cannot easily determine which contributions are “commercial,” making compliance a nightmare. Many projects might stop sharing code altogether, and individual developers could be scared off by potential legal risks. The CRA's reporting requirements would disrupt our well-established security practices, potentially making our software less secure. Centralizing vulnerability information creates a huge security risk. Worst of all, these requirements could drive smaller projects and independent developers out of the ecosystem entirely, stifling open source innovation.

In trying to improve security, the CRA might actually make things worse for everyone. This would mean serious consequences for the EU at a societal level. Essentially, regulations like this would further centralize power in the AI arms race, and drive any possible innovation out of the EU. But the implications go far beyond just the open source community. Let's consider the broader economic impact. The EU, in its rush to regulate, risks shooting itself in the foot. We're talking about potential job losses as AI companies relocate to more permissive environments like the US, or even places like Dubai, which have significant investments to promote research in the field. We're looking at missed opportunities for economic growth in a sector that's reshaping industries worldwide. The associated brain drain would also be significant. Talented developers and researchers working in the EU would see their unencumbered colleagues in the US making significantly bigger strides and think that the grass is indeed greener on the other side (of the pond). This exodus of talent through regulatory arbitrage could set the EU back years in the AI race. In trying to make AI safer and more ethical, these regulations might actually slow down even the development of beneficial AI applications. AI in healthcare could revolutionize diagnoses, and AI systems can help tackle climate change. By building barriers, we're not just hindering innovation — we're potentially denying society some incredible benefits.

Critiquing the Current Approach and The Need of AI Governance

As mentioned earlier, I am definitely not taking a stance against regulation and governance. In fact, I do think they are essential. Unregulated and unconstrained AI does in fact pose major risks to society. Deepfakes and unconstrained LLMs pose dangers at a societal level, with harms ranging from polluting elections and the propagation of dangerous knowledge and views. Unregulated AI also has the potential to propagate and worsen societal biases and discrimination, and has a high potential for misuse through surveillance and manipulation tactics. If the world was unified under one central authority, I would have certainly argued for regulation, even at this stage. But considering approaches taken in other regions like the US and China, the EU does risk falling behind in developmental terms.

There is a real challenge of adaptability in such a rapidly evolving field. Rigid regulations risk quickly becoming obsolete, stifling innovation by locking organizations into outdated frameworks. It's difficult to predict the long-term implications of AI, making it challenging to create regulations that remain relevant and effective in the future. Overregulation based on current concerns might hinder the development of solutions for unforeseen future challenges. Instead of aiming for a comprehensive regulation from the outset, a more agile approach that allows for adjustments and revisions as the technology evolves might be more effective.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), often at the forefront of AI innovation, may struggle to comply with complex regulations due to limited resources. This could stifle competition and innovation, giving larger companies an unfair advantage. Overly complex regulations can also create confusion and uncertainty for businesses, hindering investment and development. This could also lead to lengthy and costly legal battles, further slowing innovation.

Towards a More Agile Approach to AI Governance

The challenge lies in finding the right balance between fostering innovation and protecting society. This involves engaging in open dialogue between policymakers, industry leaders, and researchers to establish an adaptable regulatory framework. Instead of imposing strict rules, promoting ethical AI development through guidelines, best practices, and responsible research could be a more effective way to ensure beneficial and safe AI development in the long run.

Regulations should be adaptable to the rapid pace of AI evolution, allowing for quick adjustments as technology develops and new challenges emerge. Focussing on regulating specific applications (and sectors to a lesser extent) based on their potential risks and societal impact, rather than adopting such a blanket approach for all AI technologies.

This is by no means complete, but here are some of what I think can and should be done. Mind you, some of these are pretty out there.

- Regulatory Sandboxes: This is actually something from article 53 of the AI act. Controlled environments where companies can experiment with AI systems under real-world conditions while receiving guidance and feedback from regulators should be established. This allows for the identification of potential risks and benefits before full-scale deployment. This should be accessible for small and large companies alike, and strive to be real-world enough.

- Iterative Policy Development: Adopt an iterative approach to policymaking, starting with high-level principles and guidelines, then refining and updating them based on real-world experience, data, and feedback from individuals and groups involved in the process on the ground.

- A Continuous Learning and Adaptation Mechanism: Establish ongoing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to track the impact of AI regulations, identify emerging risks, and inform future policy iterations.

- A collaboratively edited, evolving, regulatory document?: Open source software and its associated documentation is version controlled, and its quality is constantly improved by its maintainers and contributors. This is why open source software is so successful, and also why most of the world depends on it. Why can such an idea also not exist for regulatory documents? Although no one cites Wikipedia in academic circles, it surely is one of the most pragmatic and easily digestible sources of information out there for regular people, and arguably better and more agile than any proprietary encyclopedic software ever created. Why shouldn’t regulators take the lead from this, and create something collaboratively? Moreover, isn’t regulation for the public anyway?

Taking inspiration from across the world

Two regulatory frameworks from other continents give me much more confidence compared to what the EU has been adopting.

- Singapore’s model AI governance framework — This focusses on specific AI applications and their associated risks rather than blanket regulations. The framework strongly emphasizes collaboration between the government, industry, and researchers through initiatives like the Advisory Council on the Ethical Use of AI and Data. It is also designed to be regularly updated based on technological advancements, emerging risks, and industry feedback.

- Canada's Pan-Canadian AI Strategy — Canada prioritizes the development and adoption of ethical AI principles, such as fairness, transparency, and human well-being, as guiding lights for AI development and use. It allocates significant resources to AI research, talent development, and promoting a culture of responsible AI innovation within organizations. Canada also actively engages in international forums and collaborations to share best practices and work towards globally aligned principles for ethical AI.

I believe the EU should take inspiration from what the rest of the world has been employing to foster research. Much of the talk has been centered around the GDPR, and some evidence of the Brussels effect has been observed, with global corporations adapting to the stricter standards imposed on them. But as of recently, corporations seem to be rallying against it, many of them outright refusing to operate in the EU because of the restrictions imposed.

Conclusion

The European Union's ambition to lead in ethical AI is commendable, but its current trajectory risks hindering the very innovation it hopes to foster. While addressing the potential risks of AI is essential, the current approach, characterized by the AI Act and the CRA, reeks of premature and overly rigid regulation. This approach threatens to stifle the startups and SME ecosystem with burdensome compliance, discourage open-source collaborations vital to AI advancement, and trigger a brain drain of talent seeking less restrictive environments.

I argue that the EU should consider a more agile model. This requires prioritizing flexible, iterative guidelines that adapt alongside technological progression; with regulatory sandboxes for real-world testing and refinement, and actively seeking international collaboration for drafting the regulation. The EU should find inspiration in models like Singapore's and Canada's, which demonstrate that responsible AI development need not come at the cost of innovation.

Thanks for staying with me! Consider subscribing to my writings on substack, or commenting there — Here's a link.